Scapegoat

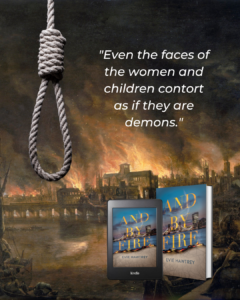

In the days and weeks following the 1666 Great Fire of London, there was tremendous civil unrest in England. The destruction of London had taken place on such a massive scale (80% of what had been contained within the city walls was destroyed, including 13,200 houses burned or demolished to establish firebreaks) that the population simply couldn’t accept it had been an accident. The stage was, thus, set for someone—anyone—to be tried and punished for starting the fire. In other words, a scapegoat.

In my novel, And by Fire, the character of Etienne Belland, a royal fireworks maker, is accused of starting the Great Fire by a group of angry shopkeepers. These accusations are not fictional. Etienne was indeed confronted, and the details of what he was asked as well as his replies are chronicled in Cobbett’s Complete Collection of State Trials, (Vol VI, Charles II, pg. 847-8). Fortunately for real-life Etienne, the plotline of And by Fire, and for my historical heroine, Lady Margaret Dove, things were taken no further.

Sadly, the same cannot be said for another young Frenchman—this one arrested while trying to leave the country. He became the man blamed and tried for starting the Great Fire of London. And hanged for it.

His name was Robert Hubert and, “when questioned he confessed that he had quite deliberately started the Fire of London” (Tinniswood, Adrian, By Permission of Heaven: The True Story of the Great Fire of London, pg. 163)

Pretty much everyone who had contact with Hubert before and during his trial felt that there was something seriously wrong with him and with his confession—which changed multiple times. “‘Nobody present credited anything he said,’ the Earl of Clarendon later recalled. Lord Chief Justice Kelyng, a formidable figure with a reputation for sternness, heard the case at the Old Bailey and told Charles II that Hubert’s story made little sense: ‘all his discourse was so disjointed that he did not believe him built’” (Id.)

In the present time we have considerable literature and numerous studies on the phenomenon of false confessions. Factors can include attention-seeking/desire for celebrity as well as emotional vulnerability or mental handicap that make it hard to withstand skillful interrogation. As a result, the modern-day British police cannot interrogate a person with a recognized intellectual vulnerability without an ‘appropriate adult” present.

Sadly, for Hubert there were no such safeguards in 1666. Despite the ample evidence suggesting he had mental health issues—including testimony from Lord Hollis and Dr. Durell, the former Dean of Windsor, who “gave evidence that he was a lunatic”—Hubert was found guilty and sentenced to hang (Hansom, Neil, The Dreadful Judgement: The True Story of the Great Fire of London, pg. 281)

When the Lord Chief Justice went to King Charles II to lay before him evidence that Hubert’s confession was likely false and offer the King a chance to act to save the man from being hanged, the King declined to act.

The reason is as simple as it is grim—“Hubert was a convenient scapegoat. And it was hoped that when he was hanged, the swirling talk of plots and conspiracies as well as mob violence against foreigners in the ruins of London might die with him. [Id. pg. 285]

Outstanding content—educational and easy to follow. Keep it coming!